Power of the Powder

How Decades of Shale Wisdom Guide Anschutz in Powder River

Drilling is never simple in the Powder River Basin, with its rugged terrain and federal red tape. But Anschutz Exploration is pushing for scale: more rigs, bigger pads and shared infrastructure to lower costs and unleash the basin’s potential.

Chris Mathews | Aug 03, 2025

Anschutz Exploration, Wyoming’s top oil producer, is pushing Powder River Basin development to new heights.

That’s no small feat in the Rockies, where regulations are tight and operating conditions are challenging.

The basin’s core spans some of the most remote, rugged and sparsely developed terrain in the Lower 48. Basic infrastructure, like power and water, can be limited or entirely absent, more a privilege than a guarantee.

Taming this wild area takes trial and error, repeatability and efficiencies of scale. It requires a “reservoir-up” mindset, emphasizing rock quality, mineralogy, pressure and fluid properties, according to Bill Knox, Anschutz’s senior vice president of operations.

Success requires tapping expertise from basins in the U.S. and abroad. It demands a multi-rig program that drills dozens of horizontal wells each year. It involves learning, refining and returning the next year even better equipped.

All of these are ingredients in the complex recipe that is unlocking the Powder River Basin horizontal play, according to Anschutz.

Anschutz drills around 65 new Powder River wells per year, executives told Oil and Gas Investor.

“If you’re drilling 65 wells a year, you’ve got 65 verticals, 65 curves, 65 laterals,” said A.J. Phillips, Anschutz’s senior vice president and CFO. “You’re able to capture those learnings in real time and apply it to the next well.”

Anschutz is also active in Utah’s Uinta Basin and Colorado’s Piceance, but the Powder River commands most of the company’s focus. However, many of Wyoming’s other leading producers EOG Resources, Continental Resources, Devon Energy and Occidental Petroleum are currently directing their resources toward other plays.

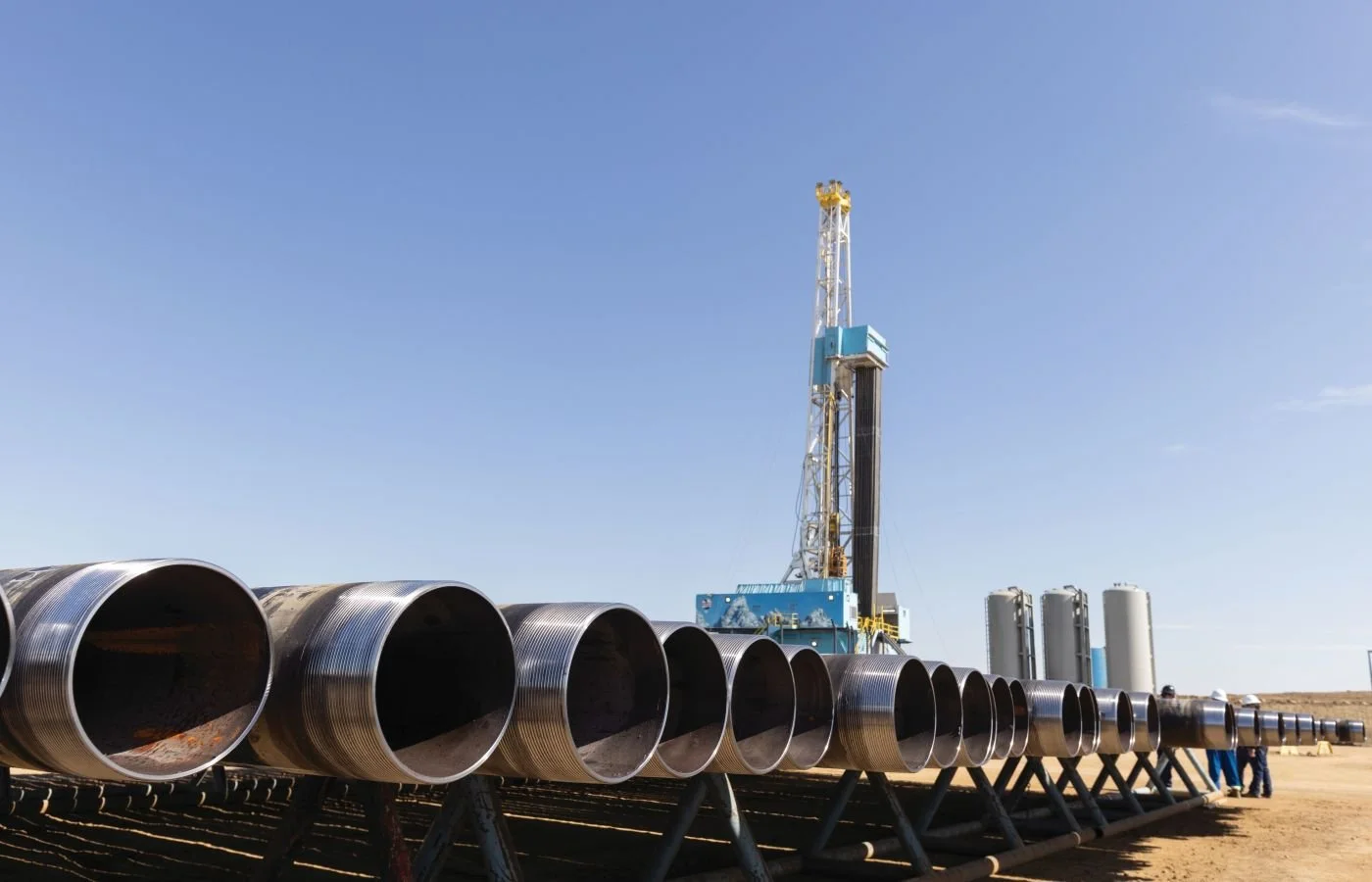

Anschutz Exploration Corp. drills its first 3-mile laterals on the Grumpy Fed pad in Johnson County, Wyoming, on June 11, 2025. (Source: Matt Idler/Hart Energy)

Those large, multi-basin producers have their hands full elsewhere, namely the Permian Basin. Even their other Rockies assets—Continental, EOG and Devon in the Bakken and Oxy in the D-J—attract greater resources than the Powder.

Without those efficiencies of scale, public producers have a higher cost to develop the Powder River. Wells drilled in the Powder’s Niobrara Shale, the basin’s top drilling target, break even at around $60/bbl, says Ryan Hill, principal analyst at Enverus Intelligence Research.

Anschutz is the largest, closest thing to a Powder River Basin pure play, all-in on driving efficiencies and lowering costs across the expansive play.

Without revealing specifics, Anschutz CEO Joe DeDominic said the company’s Powder River breakevens are well below $60/bbl.

U.S., international lessons learned

Each “emerging” horizontal oil play benefits from lessons learned by tinkering and experimentation in earlier plays. Techniques honed in the Bakken were later applied to the Eagle Ford, then refined further in the Permian.

Newer horizontal plays like the Powder River and Uinta basins are reaping the rewards of that accumulated experience.

Denver-based Anschutz is applying centuries’ worth of conventional and unconventional expertise to the Powder River’s oily stacked pay.

The Anschutz team brings experience from basins like the Eagle Ford, Bakken, D-J, Marcellus and even international exploration to rural Wyoming.

DeDominic is a geologist and seasoned executive whose career spans major upstream basins in the U.S. and abroad. He started his career with Occidental, where he focused on Colombia, Libya and the Williston Basin, eventually serving as president and general manager for Oxy’s Williston operations.

"You could easily see 20, 25 rigs running [in the Powder]... That may seem small, but that's going to grow the production because the basin's current production is not very high."

—Joe DeDominic, CEO, Anschutz Exploration. (Source: Anschutz Exploration)

DeDominic’s connection to Anschutz dates to 2010, when Oxy acquired Anschutz’s assets in the Williston for $1.4 billion. The deal helped DeDominic build a relationship with billionaire owner Phillip Anschutz.

Oxy also gave DeDominic experience in executing major exploration projects under tight budgetary constraints.

“How do you make [exploration] work? It’s the one big discovery or big project that then pays for the five, six or 10 that didn’t work,” he said. “But you kept your costs low going in and you also need a good team to do it.”

Before joining Anschutz in 2014, DeDominic worked as senior vice president and COO of Sanchez Energy, a large player in the South Texas Eagle Ford and Austin Chalk plays. During his tenure with Sanchez, he briefly overlapped with A.J. Phillips and Bill Knox.

“That’s how we all met and worked together initially,” DeDominic said.

Knox brings offshore and international experience from his tenure at Hess Corp. He also previously worked for Grayson Mill Energy when the company was focused on the Powder River, before an eventual pivot to the Bakken.

“What interested me about that is when I was at Hess, we had looked at the Powder River from a new venture standpoint back in 2010, 2011,” Knox said.

“[The Niobrara] drills like a lot of other shales. It has some different nuances from a clays standpoint, but the depths are very similar. The compressive strengths of the rock properties are very similar, so we can apply a lot of best practices from other plays,” —Bill Knox, senior vice president of operations, Anschutz Exploration. (Source: Anschutz Exploration)

“I remember thinking at the time, ‘Wow, this is a great basin, a great place to work,’” he continued. “I don’t know why people really haven’t unlocked this.”

The Anschutz team has tried to avoid becoming an “Oxy shop” or a “Sanchez shop,” Phillips said. It has tried to assemble a team with diversity of thought and experience across a range of plays.

One challenge in the Powder River was fluid loss associated with drilling the vertical section of a wellbore. It helped Anschutz to have a team that’s drilled the Eagle Ford, or Marcellus, or the depleted parts of the Bakken, to know how to handle pressure-depleted rock formations.

“It’s very easy to apply those best practices and pull those in really immediately,” Knox said.

If Knox could build engineers from scratch, he said he’d send them to train in the Haynesville Shale, with its high temperature, high pressure conditions and wellbore stability challenges.

Infrastructure build-out

There are billions of barrels of recoverable resources left untapped in the Powder River. Getting them out of the ground is easier said than done.

Drilling inputs, like sand proppant and gravel to construct roads, are in high demand but low supply across the basin. Anschutz sources certain needs from inside the basin, but a lot still needs to be hauled in via trains and trucks.

Anschutz mixes and matches its suppliers and vendors to help lower costs, too. Its drilling rigs, for example, are supplied by Cyclone Drilling, a family-owned firm based in Gillette, Wyoming.

Cyclone Drilling’s Rig No. 36 drills AEC’s first 3-mile laterals on a pad in Johnson County, Wyoming, on June 11, 2025. (Source: Matt Idler/Hart Energy)

An Anschutz frac site can host upwards of 40 workers and up to two dozen service providers.

Access to water is among the basin’s top challenges. The Powder River region is primarily semi-arid and dominated by grasslands and sagebrush shrublands.

Water is scarce in the basin. Surface water features like lakes, ponds and streams make up less than 1% of the basin’s surface area, according to a 2005 report prepared for the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

The Powder River itself is often portrayed as “a mile wide, an inch deep, too thin to plow and too thick to drink.”

Powder River oil wells produce very little water, unlike wells drilled in the Permian Basin, where too much produced water has evolved into major headaches for operators.

But the need for water in the basin is great. Anschutz will pump over 100 bbl of water per minute to complete a single Powder River oil well.

For a company drilling 65 new wells a year, the volumes add up fast. Relying on 130-bbl water trucks just isn’t practical; a single truck would be emptied in about a minute at that rate.

To keep pace, Anschutz needed larger-scale water infrastructure and efficient recycling to avoid constant, costly and disruptive trucking bottlenecks. Few things draw the ire of otherwise supportive landowners faster than the constant disruption of oilfield trucking, Knox noted, so reducing traffic is key to longevity.

Anschutz has invested in building out two large-scale water storage and recycling facilities capable of storing millions of gallons of fresh and produced water. Instead of trucking, water is piped from the centralized facilities to well pad sites.

AEC has invested heavily in building water storage and recycling facilities across its Powder River Basin positions. Water is piped from centralized facilities to well pads for completions. (Source: Matt Idler/Hart Energy)

The company has been intentional about acquiring and developing contiguous acreage blocks to take advantage of centralized water infrastructure.

“That’s a direct correlation: being able to use recycled produced water can reduce costs, which supports our economics," Phillips said.

“If you’re drilling 65 wells a year, you’ve got 65 verticals, 65 curves, 65 laterals. You’re able to capture those learnings in real time and apply it to the next well.” — A.J. Phillips, executive vice president and CFO, Anschutz Exploration. (Source: Anschutz Exploration)

“Being able to use our own gravel from surface that we own to help lower the cost of a pad, I’d say [there’s] a significant benefit there,” he said. It can cost well over $1 million to build out a well pad site before a well gets drilled, Knox said.

EOG has also invested heavily in centralized water storage and reuse systems, as well as pipelines for water transportation. The investments reduce EOG’s freshwater use and truck traffic in the basin, the company said in investor filings.

Niobrara, Mowry shales

Anschutz is pushing for full-scale development of the Niobrara and Mowry shales, which are widespread targets across the basin.

The company is the most active developer in the Powder’s Niobrara bench today, according to Wyoming state data. Niobrara is generally encountered around a vertical depth of 9,000 ft to over 11,000 ft.

From an operations standpoint, the Niobrara is a “very comfortable and familiar shale,” Knox said.

“It drills like a lot of other shales. It has some different nuances from a clays standpoint, but the depths are very similar. The compressive strengths of the rock properties are very similar, so we can apply a lot of best practices from other plays,” he said.

Anschutz and EOG Resources are the two operators pushing full-scale development of the Niobrara today. There are certain areas of the Powder River Basin where Niobrara development is in full swing, like in Converse County to the south of the basin. Shale targets are still being delineated in the north of the basin.

“Delineating is a good thing because we’re learning things about benches within the Niobrara,” Knox said.

An OGI analysis of 10 of Anschutz’s Niobrara wells completed across the basin in 2024 shows average IP rates of 1,055 bbl/d of oil. Those 10 wells have produced a cumulative 1.6 MMbbl of oil since coming online last year.

“We want some consistency, and we want results that are repeatable so you can then put a 5- or 10- or 15-year program together,” DeDominic said.

An Anschutz frac site can support up to 40 workers and dozens of different services providers. (Source: Matt Idler, Hart Energy)

Consistency and repeatability take time to develop. There simply aren’t as many horizontal wells drilled in the Powder River Basin compared to the other major plays.

That’s especially true in the deeper Mowry Shale, where development is in its early stages. Mowry pay is encountered at around 10,000 ft to over 12,000 ft across the basin.

Operators are still working to unlock the recipe for success in the Mowry. In situ bentonites create an effective frac barrier within the rock and have challenged drilling plans in the past.

“We’re very excited about it. We feel like we have a lot of Mowry,” Knox said.

Select Mowry wells display the bench’s promising upside. Anschutz’s Flying V Fed #4677-24-14-1E MH came online on July 27, 2024, with a 10,000-ft lateral.

In a 24-hour IP test, the Mowry well produced 2,056 bbl of oil and about 1.5 MMcf of natural gas.

From July 2024 through April 2025, it produced more than 279,000 bbl of crude—or about 1,000 bbl/d.

That exceeds the performance of many top-tier operators in the Permian Basin, where average wells typically yield around 200,000 bbl of oil over their first 12 months of production, according to data from Novi Labs.

Anschutz is pushing Powder River shale development to new heights. In mid-June, the company was drilling its first 3-mile laterals in Johnson County, Wyoming, in the northern Powder.

The three-well Grumpy Fed pad includes one well targeting the Niobrara and two landing in the Mowry.

The Sandstones

In addition to the Niobrara and Mowry, the Powder River is home to several prolific sandstones and semi-conventional benches, like the Turner, Shannon, Parkman, Sussex and Teapot.

Long before oil was discovered in the Permian Basin, producers were targeting the Powder River’s shallow sandstone zones. The Salt Creek Dome field, discovered in 1889 near Midwest, Wyoming, was among the state’s first major discoveries. The first Salt Creek wells targeted the Shannon sandstone.

The adjacent Teapot Dome Field gave its name to the infamous Teapot Dome scandal, a corruption case in the 1920s in which President Warren Harding’s administration secretly leased federal oil reserves in Wyoming and California to private companies in exchange for bribes.

A Senate investigation exposed the fraud, sending Interior Secretary Albert B. Fall to prison, tarnishing the Harding administration and spurring stronger oversight reforms.

Today, Powder River producers are applying horizontal techniques to these sandstone zones and producing compelling results.

Apart from the Niobrara and Mowry benches, Anschutz was most active in the Sussex bench last year. Anschutz’s Lucy Fed # 3671-35-26-3 SXH (10,000-ft lateral) targeted the Sussex Formation in Converse County, Wyoming, at a vertical depth of around 9,700 ft.

The Sussex well IP’d at 2,539 bbl/d of oil after coming online in June 2024. Through April 2025, it had produced over 256,000 bbl of crude.

Access to the sandstone zones “was a huge advantage” to Anschutz when the company was ramping up development, DeDominic said. Many of the targets are shallower than the Niobrara and Mowry, and they require softer completions than the tight shales.

“They generally drill and complete very well, and the returns are stellar,” DeDominic said. “That really allowed us to step up, grow the company and spend the time to learn more about the shale.”

These sandstone zones are prolific but not as homogeneous as the shale targets. They come and go in strips, bands and pockets across the basin. They’re also historically more depleted reservoirs, so they offer less upside than the less developed tight shale zones.

From an inventory standpoint, “The sandstones are really well mapped out and in a lot of cases, completely drilled up,” said Brandon Myers, head of research for upstream analytics firm Novi Labs.

“The Mowry is very underexplored, and the Niobrara is very early stages, as well,” Myers said.

But as Anschutz focuses on drilling the Niobrara and Mowry, it’s easier for the company to come back to an existing well pad to consider shallower sandstone wells in the future, Phillips said.

“While prevalent in the basin, it takes deep technical analysis to understand where [sandstone] locations are economically viable,” he said.

Bill Knox, senior vice president of operations (left) and A.J. Phillips, senior vice president and CFO (right). (Source: Matt Idler/Hart Energy)

Powder River’s outlook

The outlook for Powder River oil depends on who you ask. Analysts agree it remains more expensive to develop than the Permian, or even the Bakken and D-J.

Powder producers are quicker to respond to lower prices given the higher development cost.

There were 15 rigs active in the week ending on April 4, the week of the Trump administration’s “Liberation Day” tariff announcements. WTI prices dipped to below $60/bbl but recovered to nearly $70/bbl by mid-July.

Since then, Powder producers have dropped five horizontal rigs, according to Baker Hughes data.

But for a basin that’s produced oil and gas for well over a century, the Powder River Basin still has a long expected lifespan.

Continental Resources President and CEO Doug Lawler recently told Hart Energy that the Powder River Basin has “several billion barrels of resources to be mobilized” across its many stacked zones.

As U.S. producers jockey for new drilling locations, especially in the Permian, the expansive and undeveloped Powder has attracted interest.

“There’s a lot for the rock left to give,” Phillips said.

But succeeding in the basin will require millions of dollars of investment in infrastructure, materials and R&D.

Devon Energy continues to invest in science and delineation of its vast Powder asset, while prioritizing stronger returns in the Permian and Bakken, CEO Clay Gaspar said during an earnings call this spring.

It will require a mobilization of workforce. Wyoming Gov. Mark Gordon told OGI that his administration aims to give workers tools to reskill from the state’s legacy coal industry to work in oil and gas, and even emerging markets like nuclear energy.

As Anschutz has described, success will demand trial and error, repeated reinvention and a scale of execution the Powder River hasn’t seen in decades.

A Cyclone Drilling employee scales Rig No. 36 on an Anschutz pad in Johnson County, Wyoming. (Source: Matt Idler/Hart Energy)

DeDominic thinks the Powder will eventually follow a similar path as the Permian: increased consolidation and rig activity.

“You could easily see 20, 25 rigs running, which seems tiny compared to many other basins in the Lower 48," DeDominic said. “That may seem small, but that’s going to grow the production because the basin's current production is not very high."

Anschutz, for its part, also sees opportunities outside of Wyoming. The company holds gassy assets in Colorado’s Piceance Basin, which could be attractive in a rising commodity price environment.

The company is also exploring the Uinta Basin’s deeper Mancos Shale in Utah. It’s another large, contiguous target in Utah, like the Niobrara and Mancos in other Rockies states, DeDominic said.

“It’s Anschutz Exploration Corporation—exploration is part of the company’s name, and we’ll continue to do that,” he said.